The High Line: An Old Railroad Line Becomes a Park

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

It’s pretty common to hear about instances in which people take over a natural area, building over the plant life and forcing the animals to find other homes. It’s not even that rare to see places where clumps of grass sprout through cracked walls as nature returns to a site that humans have abandoned.

But how often do you hear about a place that, long after the people who built it have left and forgotten about it, becomes a natural “secret garden” that can inspire an entire community to preserve its beauty? And do you think something like that could ever happen in the middle of a city as crowded as New York?

The High Line is a story about how new environments can spring up in the most uninviting places--even on a forgotten railroad track 30 feet over some of the busiest streets in the world--and how, with hope, dedication, and persistence, people can rediscover and save these special intersections of human and nature’s creativity.

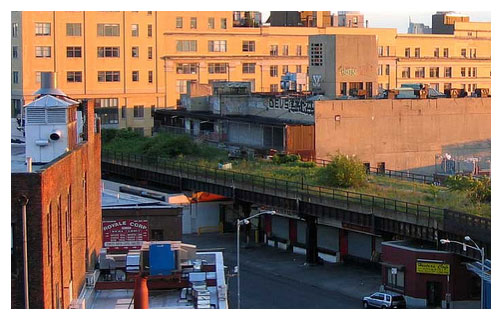

The High Line was built in the 1930s as a freight rail to transport goods to the West Side of Manhattan in New York, a district known for its warehouses, meat-packing plants, and other food processors. Replacing a street-level rail line that had led to so many accidents that its route was called "Death Avenue," the High Line ran through the center of the city blocks and was elevated 30 feet up to avoid pedestrians and carry freight directly through the second and third floors of many factories. As interstate trucking gradually replaced rail traffic over the next few decades, however, the line fell into disuse. The last train ran on the High Line in 1980. The abandoned track soon became forgotten by the people it had served, as the neighborhoods it crossed transformed from the city's industrial heart into residential, shopping, and art hot spots.

In the wake of human desertion and undisturbed by the rumble of boxcars, birds began to visit the abandoned rail line, depositing seeds from fruits they had eaten. Other seeds floated up on the wind, resting next to bits of vegetation that had been left on the tracks by the long-gone freight cars. In the sun and the rain, the seeds sprouted, grew, died, and decomposed. Little by little they created a thin layer of soil over the cast iron and wood, and new seeds germinated in the soil to become grasses, wildflowers, scrub bushes, and even trees.

Nature was creeping over the High Line, but at the same time, landlords concerned about their property values were organizing to have the obsolete structure taken down. The mayor, in the middle of an effort to revitalize the city, signed demolition papers.

In 1999, at a community meeting to discuss the rail line's fate, two neighbors realized they shared an interest in trying to save the 1 1/2-mile-long rail. Robert Hammond and Joshua David soon formed Friends of the High Line, dedicated to recognizing and preserving the structure. Around the same time, a local photographer named Joel Sternfeld discovered the High Line, and securing rare permission to walk through it, began a series of photographs taken at every season and in every kind of weather to capture and share this "absolutely magical ... secret world."

Soon the grassroots campaign attracted the attention of actors, artists, and writers who had moved into the area, and then of the media, and local civic and business leaders. Three years after the group's formation, the city decided to preserve and reuse the High Line.

Since then, a new challenge has presented itself: how to transform the raw, beautiful strip of wilderness in the heart of New York City into an accessible, safe park for the public. Concerns ranging from the presence of poisonous plants to the stability of the rail line's aging infrastructure made it impossible to just run down a ladder and let people climb up to the High Line. After an open competition to explore the space's creative possibilities, Friends of the High Line and the city selected an architectural design team as well as a group of experts in gardening, engineering, security, maintenance, public art, and other fields.

First the concrete and steel structure had to be repaired, requiring the team to pull up the overgrowth blanketing the tracks. Seeds were harvested from the overgrowth for storage and eventual replanting. The finished park will include meadow, thicket, and wetlands sections, re-creating the industrial freight rail into a 40-50-foot-wide ribbon of native plant life winding through three neighborhoods.

Construction began on the southern portion of the rail in April 2006, and in June 2009 Section 1 of the park was opened to the public. Section 2 is planned to open in 2010. The ownership of the northernmost section of the line is still undecided, but it is hoped that it will be given to the city as well.

In the words of Reed Kroloff, a member of Friends of the High Line, the park represents an opportunity to "borrow [the High Line] from an earlier generation, clean it up in ours, and hand it to the one that follows us." Even if the millions of people visiting it in the following decades never know how close this iconic urban park came to becoming just another pile of rubble, the High Line will remain an inspiring example of the power of citizen activism and the possibility to join the best of nature to the best of humanity.

For more information on The High Line go to:

The High Line and Friends of the High Line:

www.thehighline.org

The Public Information Exchange,

""High Line":

www.pieaia.org

Sundance Channel,

"High Line Stories":

www.sundancechannel.com